A world without nuclear weapons would be less stable and more dangerous for all of us. (Margaret Thatcher)

Nuclear strategy involves the development of doctrines and strategies for the production and use of nuclear weapons. As a sub-branch of military strategy, nuclear strategy attempts to match nuclear weapons as means to political ends. In addition to the actual use of nuclear weapons whether in the battlefield or strategically, a large part of nuclear strategy involves a threat to use as a bargaining tool to prevent/ limit wars. Many strategists argue that nuclear strategy differs from other forms of military strategy because the immense and terrifying power of the weapons makes their use in seeking victory in a traditional military sense is impossible. Perhaps, an important focus of nuclear strategy has been on determining how to prevent and deter their use.

KEY STRATEGIC TERMS

MAD

The United States was the first to successfully develop the atomic bomb and the first to show the bomb’s level of devastation when it used two in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan during 2nd WW. Other nations tried to catch up. Within eight years, the USSR had its own nuclear weapons. The ideological conflict between capitalism and communism sustained tensions between the U.S. and the USSR. It was soon clear that both sides had built and stockpiled enough nuclear warheads that the U.S. and USSR could wipe out each other (and the rest of the world) several times over. They had reached nuclear parity, or a state of equally destructive capabilities.

As a result, the nuclear strategy doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) emerged in the mid-1960s. This doctrine was based upon the size of the countries’ respective nuclear arsenals and their unwillingness to destroy civilization. Ironically, it was this powerful potential that guaranteed the world’s safety: Nuclear capability was a deterrent against nuclear war. Because the U.S. and the USSR both had enough nuclear missiles to clear each other from the map, neither side could strike first.

The doctrine of MAD guided both sides toward deterrence of nuclear war. It could never be allowed to break out between the two nations and resulted in Cold war between two super powers.

First Strike and Second Strike

In nuclear strategy, a first strike is a preemptive surprise attack employing overwhelming force. First strike capability is a country’s ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where the opposing side is left unable to continue war after being hit by the first strike. The preferred methodology is to attack the opponent’s launch facilities and storage depots first. The strategy is called counterforce.

In nuclear strategy, a second-strike capability is a country’s assured ability to respond to a nuclear attack with powerful nuclear retaliation against the attacker. To have such an ability (and to convince an opponent of its viability) is considered vital in nuclear deterrence, as otherwise the other side might be tempted to try to win a nuclear war in one massive first strike against its opponent’s own nuclear forces. The crucial goal in maintaining second-strike capabilities is preventing first-strike attacks from taking out a nation’s nuclear arsenal, allowing for nuclear retaliation to be carried out. The nuclear triad is a way for countries to diversify their nuclear arsenals in order to better ensure second-strike capability.

Submarine-launched ballistic missiles are the traditional, but very expensive, method of providing a second strike capability, though it needs to be supported by a reliable method of identifying who the attacker is. Using SLBMs as a second strike capability has a serious problem, because in retaliation for a submarine-launched ICBM, the wrong country could be targeted, and can cause a conflict to escalate. However, implementation of second-strikes is crucial to deter a first strike. Countries with nuclear weapons make it their primary purpose to convince their opponents that a first strike is not worth facing a second strike.

(No) First Use

No first use (NFU) refers to a pledge or a policy by a nuclear power not to use nuclear weapons as a means of warfare unless first attacked by an adversary using nuclear weapons. Earlier, the concept had also been applied to chemical and biological warfare. As of October 2008, China and India have publicly declared their commitment to no first use of nuclear weapons. China was the first to propose and pledge NFU policy when it first gained nuclear capabilities in 1964, stating “not to be the first to use nuclear weapons at any time or under any circumstances”. .However, some scholars and observers have questioned the credibility of India’s NFU policy. India’s NSA Shivshankar Menon signaled a significant shift from “no first use” to “no first use against non-nuclear weapon states” in a speech on the occasion of Golden Jubilee celebrations of the National Defence College in New Delhi on October 21, 2010, a doctrine Menon said reflected India’s “strategic culture, with its emphasis on minimal deterrence”.

Difference between First Strike and First Use.

As part of nuclear strategy, first strike is a massive initial attack intended to destroy all or most of opponent nation’s strategic nuclear weapons and cripple its ability to retaliate. Whereas, first use is the first employment of nuclear weapons; not necessarily, for complete destruction of nuclear weapons.

Massive retaliation

Massive retaliation, also known as a massive response or massive deterrence, is a nuclear strategy in which a state commits itself to retaliate with much greater force in the event of an attack. In the event of an attack from an aggressor, a state would massively retaliate by using a force disproportionate to the size of the attack. The aim of massive retaliation is to deter an adversary from initially attacking. For such a strategy to work, it must be made public knowledge to all possible aggressors. The adversary also must believe that the state announcing the policy has the ability to maintain second-strike capability in the event of an attack. It must also believe that the defending state is willing to go through with the deterrent threat, which would likely involve the use of nuclear weapons on a massive scale. Massive retaliation works on the same principles as mutually assured destruction, with the important caveat that even a minor conventional attack on a nuclear state could conceivably result in all-out nuclear retaliation.

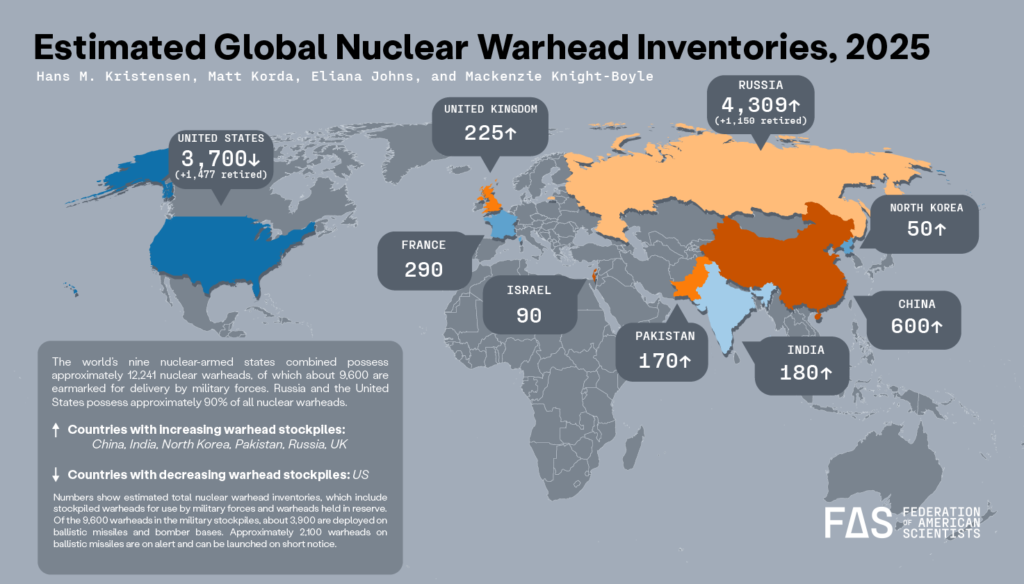

Nuclear Proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissile material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as “Nuclear Weapon States” by the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, also known as the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty or NPT. Proliferation has been opposed by many nations with and without nuclear weapons, the governments of which fear that more countries with nuclear weapons may increase the possibility of nuclear warfare.

Four countries besides the five recognized Nuclear Weapons States have acquired nuclear weapons: India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Israel. None of these four is a party to the NPT, although North Korea acceded to the NPT in 1985, then withdrew in 2003 and conducted announced nuclear tests in 2006, 2009, and 2013. Major critique on the NPT is that it is discriminatory in recognizing as nuclear weapon states only those countries that tested nuclear weapons before 1968 and requiring all other states joining the treaty to forswear nuclear weapons. Nuclear Weapon States argue that nuclear weapons are good for them but are otherwise harmful for the non-nuclear states.

Nuclear Supplier Group (NSG)

NSG is a group of nuclear supplier countries that seek to prevent nuclear proliferation by controlling the export materials, equipment and technology that can be used to manufacture nuclear weapons.The NSG was founded in response to the Indian nuclear test in May 1974 and first met in November 1975. Nations already signatories of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) saw the need to further limit the export of nuclear equipment, materials or technology. As of 2016 the NSG has 48 members.

Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT)

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a multilateral treaty that bans all nuclear explosions, for both civilian and military purposes, in all environments. It was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 September 1996 but has not entered into force as eight specific states have not ratified the treaty.

Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNW)

A tactical nuclear weapon (TNW) refers to a nuclear weapon, which is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations. This is opposed to strategic nuclear weapons, which are designed to produce effects against cities and other larger-area targets, to damage the enemy’s ability to wage war, or for general deterrence. A very small tactical nuclear weapon can have an explosive yield equivalent to 72 tons of TNT (0.072 kiloton). It could be fired from any standard 155 mm (6.1 inch) howitzer (e.g., the M114 or M198). Tactical weapons include not only gravity bombs and short-range missiles, but also artillery shells, land mines, depth charges, and torpedoes for anti-submarine warfare. Also in this category are nuclear armed ground-based or shipborne surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and air-to-air missiles

Most modern strategic nuclear weapons follow this architecture. A fission primary triggers a fusion secondary, which may subsequently initiate an additional fission stage, generating extremely high yields and compact warhead designs adaptable to multiple delivery systems.

Most modern strategic nuclear weapons follow this architecture. A fission primary triggers a fusion secondary, which may subsequently initiate an additional fission stage, generating extremely high yields and compact warhead designs adaptable to multiple delivery systems.

DETERRENCE & VARIOUS TYPES OF DETERRENCE

Concept of Deterrence

Definition. The notion is not necessarily related to nuclear matter, hence deterrence has been defined/ illustrated by various authorities in varying fashion. Simply put, deterrence aims at preventing the enemy from using his armed forces to impose his will on the opponent. Deterrence aims at exactly opposite of war in which force is used to impose one’s will on the enemy. To deter an enemy, it should be convinced that likely gains due to its action are not worth the cost that might occur.

Types of Deterrence

At times, it was thought that use of nuclear weapons could not have military objectives because of their awesome destructive capability. Later, the distinction between actual use and deterrent force of nuclear weapons began to be discussed as deterrence by punishment and deterrence by denial and their derivatives are explained below. These are also valid in non-nuclear context, although the term was evolved during nuclear discussions.

a. Deterrence by Punishment. It is aimed at preventing aggression by threat of punishment through retaliation. The 1950’s American strategies of massive retaliation and assured destruction are good examples of deterrence by punishment. The central objective of assured destruction was to deter deliberate nuclear attack upon the United States. Massive retaliation was no different from this and was more explicit in its threat of punishment as the means to deter the Soviet Union.

b. Deterrence by Denial. Deterrence by denial is defined as an attempt to prevent aggression by the adversary by convincing the aggressor through defence preparations that its aggression would face certain failure. Meaning thereby that deterrence by denial is a function of defence and not retaliation. Strategic Missile Defence capability, for example, can allow deterrence by denial.

c. Minimum Deterrence. As is the case for ‘Deterrence’, the term ‘minimum deterrence’ is one of the least understood terms but is used very often. Minimum Deterrence could be defined as “an attempt to prevent an attack through reliance on a small but secured nuclear retaliatory force capable of destroying a limited number of key targets causing unacceptable damage.’’ A country would be deemed to have minimum deterrence if after riding through the attempted first strike of the opponent would be capable enough to retaliate and cause unacceptable damage.

d. Full Spectrum Deterrence. Full Spectrum Deterrence (FSD) refers to a holistic, layered deterrence strategy designed to deter threats across the entire conflict continuum — from peace-time competition to major war — using political, informational, military, economic, technological, legal and psychological tools collectively.

It seeks to:

- prevent conflict escalation

- deny adversary success at every level

- maintain strategic stability

- and ensure survival of the state

Unlike traditional deterrence (focused only on nuclear or military force), FSD recognizes that warfare now spans conventional and non-kinetic domains including cyber, space, economics, information, and cognition. It also includes maintaining capable and credible conventional forces to deter aggression below nuclear thresholds.

For Example — South Korea vs North Korea

Purpose: To deter North Korean limited conventional or artillery warfare. South Korea maintains highly advanced air, naval and missile systems. It is also supported by US alliance forces.

AIMS OF DETERRENCE AND LINKAGE BETWEEN CONVENTIONAL AND NUCLEAR DETERRENCE

Aims of Deterrence. From these definitions, the notion of deterrence implies that instead of looking for a military victory, which used to be the war fighting strategy in the past, nuclear deterrence is expected to serve following aims:-

- To prevent an action of aggression by the enemy.

- To preserve peace and maintain status quo.

- To limit the extent and intensity of a conflict.

Linkage between Conventional and Nuclear Deterrence

a. The conventional and nuclear deterrence do not function independently, but impinge on each other in various ways. The conventional deterrence functions optimally between non-nuclear states, but becomes redundant if one of the parties in a conflict possesses nuclear capability.

b. The nuclear deterrence wields its influence and enhances conventional deterrence by precluding initiation of conflicts between two belligerents, only if both possess nuclear capability. Ironically history is replete with examples where even nuclear deterrence could not obviate occurrence of low level conflicts; however, if evaluated objectively, the nuclear deterrence had been instrumental in curtailing escalations which could have resulted in an all-out conflict/ war. Nixon believed that nuclear weapons terminated WW II and are helping to make the world safe against third world war.

c. With the introduction of tactical nuclear weapons in the realm of conventional battle field, the conventional deterrence can now be closely linked with the nuclear deterrence. This situation is likely to discourage a potential aggressor from initiating a conflict at conventional plane. However, this may lead to nuclear exchange right at the conventional level thereby nullifying the nuclear deterrence as well. Nuclear deterrence may push the conflict in LIC spectrum.

d. In order to deter conventional war, a nuclear state may maintain a certain level of conventional forces, while drawing lines for nuclear response, when these thresholds are crossed. This is the essence of nuclear deterrence, where balance of conventional forces is clearly against the weaker side.

e. Larger force differential on conventional plane between the two belligerents will lower the nuclear thresholds. Conversely, maintaining balance is essential to have a higher threshold. Maintaining balance does not necessarily mean maintaining of equal conventional forces.

INGREDIENTS OF DETERRENCE AND THE LIMITATIONS OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE

Essential Ingredients of a Credible Deterrence. In order to prevent the failure of deterrence, it must possess three essential ingredients:-

a. Capability. The capability is related to possession of nuclear weapons, delivery means and related technology to actualize the threat. The capability requirement of deterrence, however, cannot be seen exclusively in terms of physical capacity to inflict harm or deprivation upon another party. This is an essential part of deterrence, but will not suffice if the challenger is unable to assess properly the likely relationship of gains and losses dependent upon any move he might make. Thus a successful deterrence posture must aim to ensure that the threatened costs are sufficiently high to convince a potential challenger that the action would not be worthwhile.

b. Credibility. This implies that it is necessary to influence the adversary’s expectations in such a way that he believes that deterrence threat would actually be implemented, and that he would certainly incur the specified penalty in the event of any transgression. In making the threat believable, lies the art of deterrence. Thus it is apparent that an optimum deterrence would be the one where the recipient of a threat is absolutely certain that in the event of his taking action, unacceptable costs would be inflicted upon him almost automatically. This requirement is more subjective in nature and is dependent on two sub factors i.e. second strike capability and political will.

c. Communication. The first requirement of an effective deterrence posture is that the adversary be made aware of precisely what range of actions are prohibited and what is likely to happen if he disregards them. Clear and careful communication is therefore a necessity. The communication may make full use of a variety of channels and methods of communication. Public statements, private messages and demonstrative action may all have to be used to convey accurately and successfully a particular message to a rival

d. Limitations of Nuclear Deterrence. Nuclear deterrence, however, does not lie in the weapon itself. It is in the mind of a leader who has the authority to press the button when the time comes. If the adversary is willing to pay the price, the deterrence will not work. It is therefore, different from person to person, country to country and from time to time. The cost benefit ratio can keep altering with a change of political leaders in a country. Nuclear deterrence is not a law of physics, which will always be true. It is based on empirical data and, therefore, not beyond doubt. The chances of its failing will always be there, no matter how remote they may be.

NUCLEAR THRESHOLD

The “nuclear threshold” refers to the point where a country has the technical capability to quickly build nuclear weapons but hasn’t yet, or the level of nuclear test yield deemed acceptable; it describes nations like Iran or Israel that possess advanced nuclear tech but exercise restraint (nuclear latency). It also signifies a nation’s policy on when to use nuclear weapons, with some nations lowering their doctrinal threshold to reserve the right to use them even against conventional attacks to protect sovereignty, as seen with Russia. What might compel to contemplate the use of nuclear weapons could include the following factors:-

a. Penetration of territory by enemy forces, threatening the core areas, population centers of psycho-social importance or strategic division of the county.

b. Unacceptable degradation of the conventional forces.

c. Threat of destruction of the nuclear capability.

d. Economic strangulation due to blockade and destruction of infrastructure.

e. Decision to nuclearize the conflict by exercising ‘first use” option by the enemy.

MAJOR CATEGORIES OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS

Nuclear weapons are broadly classified by their intended use (Strategic vs. Tactical/Non-Strategic) and their design (Fission vs. Fusion/Thermonuclear), with most modern weapons using a fission-fusion-fission design, delivering massive yields via carriers like ICBMs, SLBMs, bombers, or shorter-range missiles, forming the “nuclear triad” for deterrence. Strategic weapons target deep enemy infrastructure, while tactical ones aim for battlefield use, though modern arsenals focus heavily on the strategic triad for deterrence.

- By Use/Targeting (Primary Classification)

- By Design/Energy Source (Physics)

- Key Delivery Systems (The Nuclear Triad)

By Use/Targeting (Primary Classification)

- Strategic Nuclear Weapons: Designed for long-range strikes against deep enemy targets (cities, military bases, industry) to cripple their ability to wage war.

- Delivery: Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs), Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs), heavy bombers (part of the Nuclear Triad).

- Tactical (or Non-Strategic) Nuclear Weapons (TNWs/NSNWs): Intended for battlefield use, with lower yields and shorter ranges, though none have been used in combat.

- Examples: Nuclear artillery shells, land mines, anti-submarine depth charges, short-range missiles, Davy Crockett (one of the smallest).

By Design/Energy Source (Physics)

- Fission Bombs (Atomic Bombs): These weapons derive their explosive force from the splitting (fission) of heavy atomic nuclei such as Uranium-235 or Plutonium-239. The weapons used against Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 were classic examples of this design.

- Boosted Fission Weapons: A modified form of fission weapon in which a small amount of fusion fuel is introduced to enhance efficiency and yield. This allows greater explosive power without proportionally increasing weapon size or fissile material requirements.

- Thermonuclear Weapons (Hydrogen Bombs/H-Bombs): These weapons employ a two-stage process in which a fission primary device ignites a secondary fusion stage. Fusion reactions produce vastly greater energy outputs, allowing yields measured in megatons of TNT equivalent.

- Staged Thermonuclear Weapons: Most modern strategic nuclear weapons follow this architecture. A fission primary triggers a fusion secondary, which may subsequently initiate an additional fission stage, generating extremely high yields and compact warhead designs adaptable to multiple delivery systems.

Key Delivery Systems (The Nuclear Triad)

- ICBMs (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles): Land-based, long-range missiles.

- SLBMs (Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles): Carried by nuclear submarines, offering stealth and survivability.

- Strategic Bombers: Aircraft capable of delivering large nuclear bombs over long distances.

Most modern strategic nuclear weapons follow this architecture. A fission primary triggers a fusion secondary, which may subsequently initiate an additional fission stage, generating extremely high yields and compact warhead designs adaptable to multiple delivery systems.