‘‘The rifle is the queen of weapons and its effective use is one of the greatest satisfactions available to man.’’

(Jeff Cooper)

The evolution of small arms represents a continuous interplay between chemical propellant technology, mechanical engineering, and tactical necessity. This is a comprehensive analysis of the transition from primitive gunpowder tubes to the digital, high-pressure systems of the 21st century. By examining the shifting paradigms of ignition, ballistics, and modularity, we can observe how the infantryman’s reach has expanded from 50 yards to over 600 yards, fundamentally altering the nature of the modern battlefield.

INTRODUCTION: THE PARADIGM OF INFANTRY LETHALITY

Small arms are defined as man-portable firearms designed for individual use. Their history is not merely a record of invention but a response to the “deadly zone”—the area where a soldier is at risk of enemy fire. As technology improved, this zone expanded, forcing shifts from massed Napoleonic lines to the dispersed, high-tech maneuvers of today.

PHASE 1: THE CHEMICAL GENESIS (10TH–14TH CENTURY)

The history of firearms begins in 10th-century China with the invention of fire lances—bamboo or paper tubes filled with black powder and shrapnel.

- Hand Cannons (The “Gonne”): It is the oldest type of small arms, as well as the most mechanically simple form of metal barrel firearms. Unlike many firearms, it requires direct manual external ignition through a touch hole without any form of firing mechanism. It may also be considered a forerunner of the handgun. Hand cannons first saw widespread usage in China sometime during the 13th century and spread from there to the rest of the world. By the 13th century, these evolved into metal tubes (bronze or iron) with a “touch-hole” at the breech. The earliest reliable evidence of cannons in Europe appeared in 1326 in a register of the municipality of Florence and evidence of their production can be dated as early as 1327.

- Tactical Limitation: Early hand cannons were heavy and required a two-man team or a stationary rest. The lack of a mechanical trigger meant the soldier had to hold a burning stick to the touch-hole, making aiming almost impossible. These weapons were primarily psychological, used to terrify cavalry and break ranks with noise rather than precision.

PHASE 2: THE MECHANICAL LOCK ERA (1400–1820)

The 15th century introduced the first mechanical ignition systems, allowing the shooter to maintain a steady aim with both hands.

- The Matchlock (15th c.): The first mechanical trigger. It utilized an S-shaped “serpentine” to lower a smoldering cord into a flash pan. Matchlocks were the first mechanically ignited firearms, followed by the revolutionary flintlock, which became a staple in military and civilian use for over 200 years.

- Drawback: The burning match was hazardous in rain and revealed troop positions at night.

- The Wheellock (16th c.): A complex, clockwork-like mechanism that struck pyrite against a spinning steel wheel to generate sparks. While it allowed for the first concealable pistols, it was too expensive for mass infantry issue. The wheellock mechanism was wound against the tension of a strong spring. When the trigger was pulled, a serrated wheel revolved against a piece of flint. This caused sparks to ignite the powder and discharge the bullet.

- The Flintlock (17th c.): Standardized by the mid-1600s, it used a piece of flint striking a steel “frizzen”. Flintlocks simplified ignition by allowing the lid and spark to be activated simultaneously. Sparks were produced by striking flint against iron, which ignited the gunpowder more efficiently. The flintlock system enhanced the firing speed and increased the overall reliability of firearms.

- This system reigned for over 200 years, epitomized by the British Brown Bess. Flintlock weapons were commonly used until the mid 19th century, when they were replaced by percussion lock systems. Even though they have long been considered obsolete, flintlock weapons continue to be produced today by manufacturers such as Pedersoli, Euroarms, and Armi Sport.

- Interchangeability: In 1777, the French Modèle 1777 introduced gauges and patterns, marking the first steps toward interchangeable parts and mass production.

PHASE 3: THE PERCUSSION AND RIFLING RENAISSANCE (1820–1865)

The 19th century transformed the smoothbore musket—accurate only to 100 yards—into a precision instrument.

- Percussion Ignition: In 1807, Alexander John Forsyth patented the use of fulminates (mercury fulminate) which detonated when struck. By 1830, the copper percussion cap made firearms weatherproof and reliable. The percussion cap contains a small charge of chemical in a small copper cuplike holder which can be quickly pressed onto to a nipple mounted in the rear of a gun barrel. When the trigger is pulled, the hammer strikes the cap, igniting the chemical which sparks through a hole in the nipple into the main charge in the barrel, firing the gun.

- The Minié Ball: Rifling (grooving the barrel) was historically slow to load because the bullet had to be hammered down the grooves. The Minié ball (1849) solved this with a conical design and a hollow base that expanded upon firing to grip the rifling. The Minié ball, or Minie ball, is a type of hollow-based bullet designed by Claude-Étienne Minié for muzzle-loaded, rifled muskets.

- Tactical Impact: This increased effective range from 100 yards to over 500 yards. In the American Civil War, this led to catastrophic casualties as commanders continued to use outdated Napoleonic mass-line tactics against rifled weapons.

PHASE 4: THE BREECH-LOADING AND CARTRIDGE EPOCH (1860–1885)

The transition from muzzle-loading to breech-loading allowed soldiers to reload while lying prone.

The Needle Gun: The Prussian Dreyse Needle Gun (1841) also known as a needle-rifle or needle-fire weapon—is a firearm that uses an unusually long, needle-shaped firing pin to ignite the propellant charge. The firing pin pierces the paper cartridge and strikes a percussion cap located at the base of the bullet, initiating ignition from the rear of the cartridge. This design enabled self-contained paper cartridges and significantly faster loading compared to traditional muzzle-loading rifles, marking a major step forward in 19th-century small-arms technology.

Metallic Cartridges: The shift to self-contained brass cartridges (combining bullet, powder, and primer) provided a superior gas seal (obturation) and allowed for repeating firearms like the Spencer and Winchester.

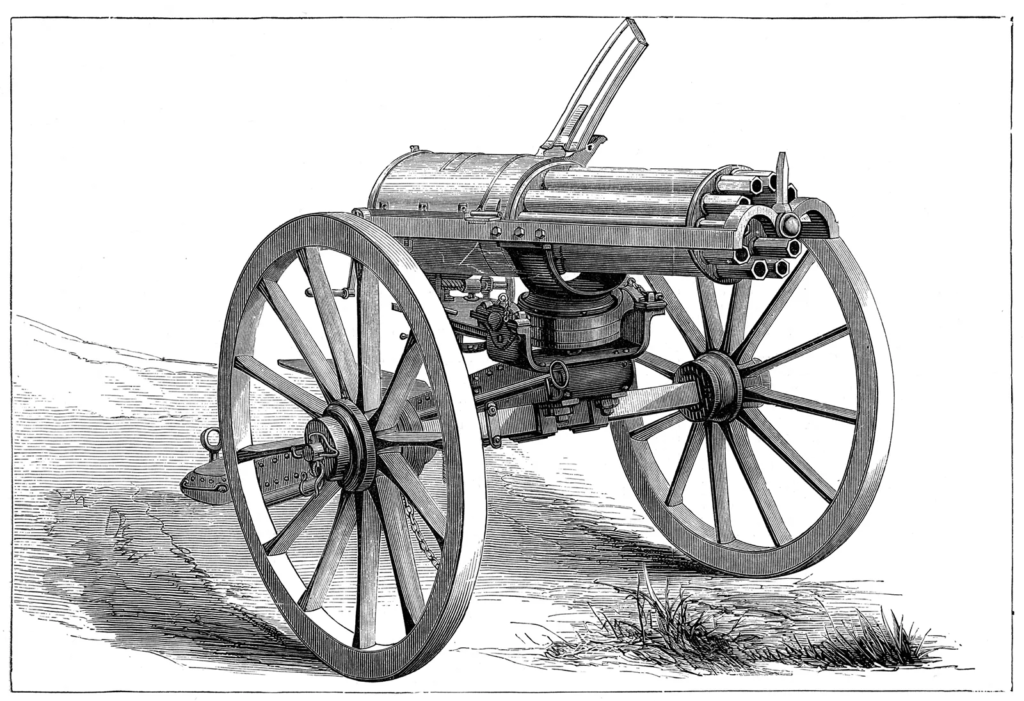

The Gatling gun: Developed during the Civil War, this multi-barrel weapon provided the first reliable sustained rapid fire, though it was still considered an artillery piece due to its weight. The Gatling gun is a rapid-fire, multi-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling of North Carolina. One of the earliest true machine-gun concepts, it served as a technological bridge between manually operated repeating arms and the fully automatic, electrically driven rotary cannons of the modern era.

- The weapon’s operation was based on a rotating cluster of barrels arranged around a central axis. A hand-cranked mechanism rotated the barrels, with each barrel sequentially passing through the loading, firing, and extraction stages. Cartridges were gravity-fed from a top-mounted magazine. As each barrel reached the firing position, it discharged a round; the empty casing was then ejected as the barrel continued its rotation. This design not only synchronized the firing cycle mechanically but also reduced overheating, since each barrel fired intermittently rather than continuously. The system eliminated the need for a single high-stress bolt and enabled sustained high rates of fire for its time.

- The Gatling gun is regarded as one of the first successful rapid-fire battlefield weapons. It saw combat use with the Union Army during the American Civil War, marking its operational debut. In the decades that followed, it was employed in multiple conflicts, including the Boshin War in Japan, the Anglo-Zulu War, and the Spanish–American War—notably during the assault on San Juan Hill. It was also used for domestic security operations such as during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, and naval forces mounted Gatling guns aboard warships for close-range defense.

PHASE 5: THE SMOKELESS POWDER AND AUTOMATIC REVOLUTION (1885–1918)

In 1884, Paul Vieille invented Poudre B (Smokeless Powder), which was three times more powerful than black powder.

- Ballistic Shift: High-velocity, small-caliber rounds (like the 8mm Lebel and .30-06) replaced heavy, slow lead slugs. Trajectories became flatter, making long-range shooting easier.

- The Maxim Gun (1884): Hiram Maxim used the recoil energy to cycle the weapon, creating the first true machine gun. By WWI, the combination of smokeless powder and automatic fire ended the era of cavalry and forced warfare into the trenches. The Maxim gun, patented in 1884 by the American-born British inventor Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim, represents perhaps the most significant single technological leap in the history of small arms. Before the Maxim, “rapid-fire” weapons like the Gatling or Nordenfelt relied on external manual power—the soldier had to physically crank a handle to chamber, fire, and extract rounds. The Maxim gun fundamentally altered this by utilizing the weapon’s own energy to perform these functions, effectively birthing the “Automatic Era.”

- Moving away from the gravity-fed hoppers of the Gatling, the Maxim utilized a flexible canvas belt (typically 250 rounds). This allowed for a continuous supply of ammunition, provided the crew could keep up with the belt-linking.

- Bolt-Action Perfection: The first practical bolt-action rifles emerged in the early 19th century, beginning with Johann Nicolaus von Dreyse’s needle-fire rifle, developed in the 1830s and formally adopted by Prussia in 1841. This weapon — often referred to as the Dreyse Needle Gun — used a paper cartridge ignited by a long firing pin (or “needle”) that pierced the cartridge to strike a primer at the bullet base. Crucially, it was breech-loading, allowing soldiers to reload and fire significantly faster than traditional muzzle-loading rifles, even from prone or covered positions. Its battlefield success during the Austro-Prussian War (1866) demonstrated the decisive tactical advantages of bolt-action, breech-loading rifles and inspired other nations to invest in similar systems.

- By the 1850s–1870s, major advances in metallic centerfire cartridges — pioneered by designers such as Joseph Needham and Béatus Beringer — enabled stronger, safer, and better-sealed breech mechanisms. This development allowed bolt-action rifles to evolve from experimental concepts into durable, service-ready infantry weapons. A key milestone was the Mauser Model 1871, the first bolt-action rifle officially adopted across the German Empire. Featuring a strong rotating-bolt design, it established engineering principles that would shape bolt-action rifles for decades. In the United States, designs such as the Winchester-Hotchkiss (1876) marked growing Western interest in repeating bolt-action systems.

- Bolt-action rifles achieved widespread adoption because they offered:

- Accuracy: The strong, consistent locking of the bolt provides precise cartridge alignment, crucial for long-range shots.

- Reliability & Durability: Simple design means fewer moving parts to fail, making them tough and long-lasting.

- Strength for High-Powered Rounds: The robust action handles powerful, high-velocity cartridges enabled by smokeless powder, enhancing range and flat trajectory.

- Ease of Use (Prone): Their design makes them easier to operate from a prone (lying down) position, vital for soldiers.

- Efficient Loading: Top-loading allowed for fast reloading with stripper clips, a major advantage in early repeating rifles.

- Adaptable for Optics: Their solid design easily accommodates telescopic sights, benefiting hunters and snipers.

- By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these advantages led to the widespread introduction of magazine-fed repeating bolt-action service rifles, culminating in iconic World War I weapons such as the Lee-Enfield (UK), Mauser Gewehr 98 (Germany), and Mosin–Nagant (Russia). These rifles combined high accuracy, solid long-range performance, and dependable battlefield reliability — establishing bolt-action systems as the backbone of global infantry firepower well into the 20th century.

- Rifles like the Mauser 98 and Lee-Enfield reached their peak, allowing a soldier to fire 15–30 aimed rounds per minute.

PHASE 6: THE INTERMEDIATE REVOLUTION AND THE ASSAULT RIFLE (1940–1990)

WWII research proved that most combat occurred within 300 meters. Full-power rifle rounds were too heavy and had too much recoil for controllable automatic fire.

The StG 44 (Sturmgewehr): Germany developed the first successful assault rifle, using an “intermediate” cartridge (7.92x33mm Kurz). The StG 44 (short for Sturmgewehr 44 or “Assault Rifle 44”) represents the single most important evolutionary leap in 20th-century infantry small arms. Developed in Nazi Germany during World War II by the prolific designer Hugo Schmeisser, it was the world’s first successful “assault rifle”—a term allegedly coined by Adolf Hitler himself for propaganda purposes. The StG 44 did not merely improve upon existing technology; it created an entirely new category of weaponry that combined the range and accuracy of a rifle with the devastating fire volume of a submachine gun.

- The StG 44 utilized a gas-operated, long-stroke piston system with a tilting bolt. This mechanism was incredibly robust and served as a direct mechanical precursor to the Soviet AK-47.

- Selective Fire: It featured a fire-control group that allowed the shooter to toggle between semi-automatic (for precision) and fully automatic (for suppressive fire).

- Manufacturing: Unlike the intricately machined rifles of the era, the StG 44 used stamped steel parts. This allowed for faster, cheaper mass production in a war-torn economy, a technique that would define post-war firearm manufacturing.

The AK-47 vs. M16: The Soviet AK-47 prioritized reliability in harsh conditions, while the American M16 utilized lightweight materials (aluminum and plastic) and a high-velocity 5.56mm round.

Specialized Squad Roles: As noted in source material, weapons like the M249 SAW were introduced to fill the gap left by the BAR, providing mobile suppressive fire to the squad. The M79 Grenade Launcher expanded the squad’s reach with explosive projectiles more portable than mortars.

PHASE 7: THE DIGITAL AND MODULAR FRONTIER (1990–PRESENT)

Modern warfare emphasizes modularity—the ability to adapt one weapon to multiple roles.

- Picatinny Rails (MIL-STD-1913): This allowed for the standardized mounting of optics, lasers, and grips, turning the rifle into a “modular weapon system”.

- Optics Revolution: The shift from iron sights to red dots (Aimpoint) and magnified optics (ACOG) significantly increased the average soldier’s first-shot hit probability.

THE NGSW PROGRAM: THE NEXT GREAT LEAP (2020–FUTURE)

The U.S. Army’s Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) program represents the most significant caliber shift in 60 years.

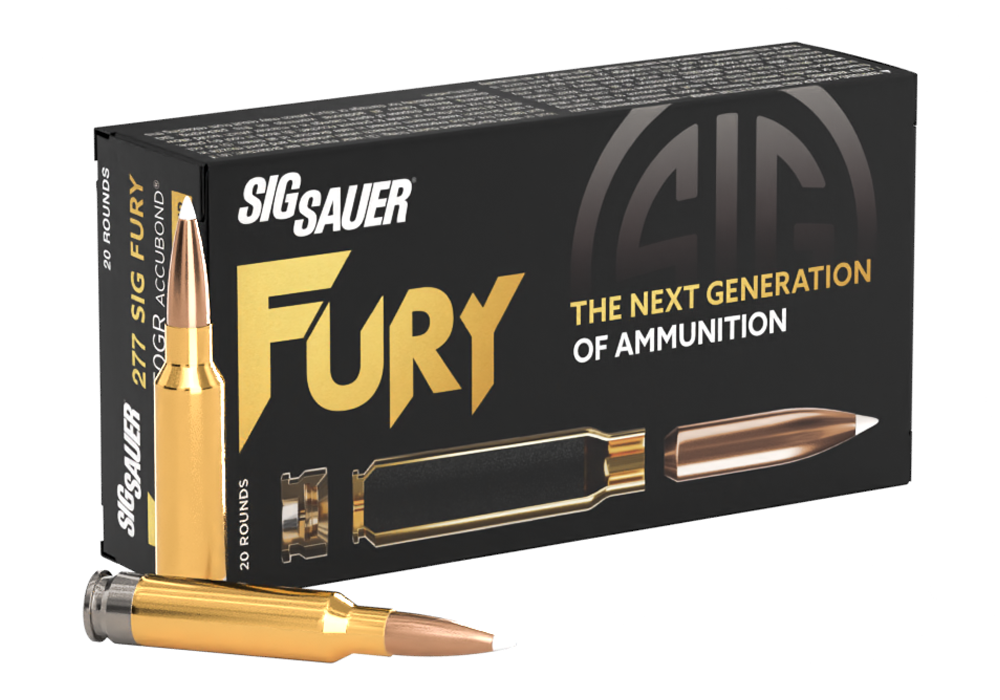

The 6.8x51mm Hybrid Round (.277 Fury): Designed to defeat modern ceramic body armor that 5.56mm cannot penetrate at range. The 6.8×51mm, commercially designated as the .277 Fury, represents the most significant advancement in small arms ammunition since the adoption of smokeless powder. Developed by SIG Sauer for the United States Army’s Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) program, this cartridge was engineered to solve a specific tactical crisis: the proliferation of advanced ceramic body armor (Level III and IV) among peer and near-peer adversaries, which rendered the standard 5.56mm NATO round increasingly ineffective at combat distances.

The primary limitation of traditional ammunition is the material strength of brass. At pressures exceeding 65,000 PSI, standard brass casings begin to deform, “flow,” or suffer catastrophic head separation. To overcome this, the .277 Fury utilizes a pioneering tri-metal hybrid construction:

- Stainless Steel Base: A high-strength steel “cup” or base allows the cartridge to withstand staggering chamber pressures of 80,000 to 90,000 PSI.

- Brass Body: The upper portion of the case remains brass to ensure traditional obturation (the casing expanding to seal the chamber against escaping gases) and to maintain a lower overall weight than a full steel case.

- Aluminum/Locking Washer: A specialized washer or internal mechanism locks the steel base to the brass body, ensuring structural integrity during the violent cycle of automatic fire.

- The .277 Fury is designed to provide “magnum” performance from a short-barreled infantry rifle. Its high-pressure nature allows the XM7 (MCX-SPEAR), with only a 13-inch or 16-inch barrel, to achieve velocities that previously required a 24-inch “precision” barrel in older calibers.

Extreme Pressure: The hybrid cartridge (steel base, brass body) handles 80,000 PSI—nearly 20,000 PSI more than traditional NATO rounds—achieving magnum performance from a short 16-inch barrel.

Smart Optics (XM157): The integrated fire-control system includes a laser rangefinder, atmospheric sensors, and a ballistic computer that provides an adjusted aiming point for the soldier.

Comparative Ballistics and Technical Summary

| Technology | Era | Typical Range | Propellant | Key Advantage |

| Matchlock | 1500s | 50 yards | Black Powder | First mechanical trigger |

| Flintlock | 1700s | 75 yards | Black Powder | Reliability, weatherproof |

| Minié Rifle | 1850s | 500 yards | Black Powder | Long-range precision |

| Bolt Action | 1900s | 800 yards | Smokeless | High velocity, rapid reload |

| Assault Rifle | 1950s | 300 yards | Smokeless | Automatic, lightweight |

| NGSW (XM7) | 2025+ | 600+ yards | Smokeless/High Pressure | Armor penetration, Smart Optics |

LATEST TRENDS IN SMALL ARMS (SAs)

General Trends

The evolution of infantry small arms has taken centuries, with every major technological leap significantly reshaping the character of warfare. Over the past two decades in particular, rapid advancements have taken place in both weapons and ammunition. The overarching design philosophy has been to make infantry weapons lighter, more compact, ergonomic, accurate, modular, and lethal, while also reducing recoil and improving reliability under combat conditions.

Some technologically advanced nations have focused on reducing caliber, weight, and recoil, while others emphasize family-system weapons platforms — where carbines, assault rifles, and light machine guns share common parts and operating mechanisms. The end goal remains constant: to equip the 21st-century soldier with a highly lethal, reliable, accurate, and lightweight weapon system optimized for diverse operational environments. In essence, modern small arms directly enhance the combat performance, survivability, and endurance of the soldier.

MODERN INFANTRY SMALL ARMS IN CONTEMPORARY ARMIES

1. Multi-Barrel / Multi-Caliber Weapon Systems

Modern modular weapons allow the operator to configure caliber and barrel length depending on mission profile. These systems enable rapid barrel or upper-receiver changes in the field, improving logistical flexibility and role adaptability (rifle, carbine, DMR, or LMG configurations).

Examples include:

- FN SCAR-L (5.56 mm)

- FN SCAR-H (7.62 mm)

Both share a common operating platform but support multiple barrel lengths and calibers — offering mission-tailored firepower without retraining the operator.

2. Folding / Concealable Sub-Machine Guns

Foldable and flexible SMGs are a growing trend, focusing on extreme compactness (like FoldAR’s 12″ folded length), enhanced modularity (B&T’s APC9 series, Magpul FDC-9/FDP-9 for pistol/SBR conversion), and advanced materials for concealability/portability, often using polymer receivers (UMP), with innovations like optics-on-when-folded (Kel-Tec SUB 2000 Gen3) and hybrid designs (B&T BWC) leading to more versatile, concealable, and user-friendly compact weapons for special units and civilian markets.

Foldable sub-machine gun designs cater primarily to VIP protection, covert operations and CQB environments where discretion and concealment are critical. The concept dates back to the 1980s when Eugene Stoner pioneered compact, folding-profile SMGs.

Modern examples include the FMG-9, a folding 9 mm weapon which, when folded, resembles an innocuous device such as a tool case — yet can be rapidly deployed for immediate engagement.

3. Bullpup Weapons with Dual-Role Capability

Bullpup-configured rifles place the action and magazine behind the trigger, allowing full-length barrels in compact frames — ideal for urban or mechanized infantry. These systems are typically gas-operated with short-stroke piston systems and rotating bolts, providing high reliability.

Features commonly include:

- Polymer housings to reduce weight

- Integrated carrying handles and sight rails

- Compatibility with optical & night-vision systems

Such rifles combine compactness, accuracy, and battlefield versatility.

4. Controlled-Burst / Family-System Assault Rifles

The INSAS family (India) is an example of a multi-role infantry weapon system consisting of:

- Assault rifle

- Light machine gun version

- Carbine variant

INSAS is based on the Kalashnikov operating principle but includes design refinements, manual gas regulation, selectable firing modes (including three-round burst in newer variants), and compatibility with under-barrel grenade launchers and bayonets. This reflects the global trend toward family-system modularity.

STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SMALL ARMS

1. Shift Toward Smaller Calibers

Recent decades have seen a global transition away from heavier calibers like 7.62 mm toward smaller, higher-velocity rounds such as 5.56 mm and newer intermediate calibers.

This shift delivers several advantages:

- Reduced weapon weight through lighter barrels and components

- Lighter ammunition, allowing soldiers to carry more rounds

- Lower recoil, improving accuracy and control in automatic fire

- Higher rate of fire and faster follow-up shots

- Improved performance in Close-Quarters Battle (CQB)

- Enhanced soldier endurance and mobility

The ultimate result is a greater sustained combat capability at the section and platoon level.

2. Caseless Ammunition

Caseless ammunition eliminates the traditional brass cartridge case, using fully combustible propellant blocks. This reduces weapon heat signature, ammunition weight, and mechanical complexity.

The H&K G11 (4.7 mm) was the most advanced caseless-ammo prototype, featuring:

- 50-round magazine

- High-rate burst capability

Although never fielded at scale, the technology remains a focus for future development programs.

3. Controlled Burst Fire

Controlled 3-round burst fire modes aim to maximize hit probability. The first round is aimed, while recoil shifts the muzzle upward — meaning burst geometry naturally walks rounds into the target zone at engagement distance. This enhances lethality while conserving ammunition.

4. High-Capacity Magazines — BETA C-Mag

The BETA C-Mag is a twin-drum magazine with 100-round capacity, compatible with:

- 5.56×45 mm NATO

- 7.62×51 mm NATO

- 9×19 mm

Some versions incorporate transparent rear housings for visual round-count monitoring. These are particularly useful in suppressive fire roles.

5. Ready-Mag Systems

Ready-mag systems attach dual magazines directly to the weapon, enabling very rapid reloads without reaching for pouches. Examples include:

- HK33E

- M16A2 variants

6. Dual-Role Rifle Optics

Modern optics like the ELCAN Specter DR feature dual magnification modes, allowing instant switching between:

- Close-Quarter reflex engagement

- Precision mid-range fire

Thus a single sight fulfills both assault and designated marksman roles.

7. Widespread Use of Polymers and Composite Materials

Modern small arms increasingly use fiberglass, polymers, and composite materials in:

- Stocks

- Pistol grips

- Handguards

- Magazines

This reduces weight and corrosion, improves ergonomics, and simplifies production. A prime example is the Steyr AUG, featuring over 20% polymer content. Transparent magazines are now common, providing real-time ammunition awareness.

8. The U.S. Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW)

The U.S. Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) program is the Army’s initiative to replace the lesser effective rifles with more lethal, longer-range weapons using a new 6.8mm ammunition, featuring the XM7 Rifle and XM250 Automatic Rifle, plus an advanced fire control optic (XM157), to give soldiers superior accuracy and armor penetration against modern threats. SIG Sauer won the contract, delivering the MCX Spear-based XM7 and XM250, incorporating 6.8mm hybrid ammo and suppressors for enhanced combat effectiveness. Following lessons from Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. Army launched the NGSW program, aimed at replacing:

- M4 / M4A1 Carbine

- M249 SAW

The program has adopted:

- 6.8 mm intermediate caliber ammunition

- New rifle and automatic rifle systems

- Advanced fire-control optics

This marks a major shift in infantry firepower philosophy.

LATEST TRENDS IN SMALL ARMS AMMUNITION

Infantry remains the decisive combat arm of modern militaries. Since infantry lethality depends heavily on small arms and ammunition, ammunition technology has become a major focus area — improving terminal effects while optimizing weight and accuracy. The latest trends in infantry small arms ammo focus on lethality, armor penetration, and advanced tech, highlighted by the U.S. Army’s shift to the powerful 6.8x51mm hybrid cartridge for its Next Generation Squad Weapons (NGSW) to defeat modern body armor, replacing the aging 5.56mm. Key trends also include developing lighter materials, eco-friendly options, smart/programmable rounds with integrated electronics, specialized bullets (like frangible), and improved propellants for better performance and reduced weight, balancing power with logistics. The move to 6.8x51mm (277 Sig Fury) is the biggest shift, using a steel-cased hybrid design to handle extreme pressure, offering double the effective range and energy of 5.56mm against advanced armor. It includes increased use of copper FMJ, frangible (for training/CQB), and tracer rounds for better battlefield awareness.

DEVELOPMENTS IN CARTRIDGE CASES

1. Plastic Cartridge Cases

Plastic (polymer) cartridge cases are a major development in ammunition, offering significant weight reduction (30-40% lighter), improved heat insulation (less chamber heating), lower cost potential, and better performance consistency than traditional brass, with the U.S. military actively adopting them for next-gen rifles like the 6.8mm NGSW, providing soldiers more rounds and reducing logistical burdens, while also improving safety by managing heat and cook-off better. The Army’s Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) program, intended to replace M16/M4 ammo, heavily features polymer-cased rounds (like True Velocity’s) for increased soldier capability.

Plastic components are increasingly used for:

- Blank rounds

- Training ammunition

- Some service rounds

These reduce cost and weight and improve corrosion resistance.

ADVANCES IN ARMOUR-PIERCING (AP) AMMUNITION

1. Tungsten-Carbide AP Rounds

Tungsten-Carbide AP (Armor-Piercing) rounds use an extremely hard, dense tungsten carbide core, often with a copper jacket, to defeat hardened steel armor and body protection, offering superior penetration over steel-core rounds due to tungsten’s high hardness and density for kinetic energy transfer. Popular in military/LE sniper calibers like .308 Win, .338 Lapua Mag, and 5.56 NATO, they deliver high impact energy, breaching tough targets effectively, though they require robust barrels and face legal restrictions in some areas. Tungsten-carbide is:

- Extremely dense

- Harder than steel

- Highly effective against body armor

Its density falls between steel and gold, making it highly penetrative.

2. Titanium Rounds

Titanium rounds aren’t common for actual firearms due to hardness, cost, and low density, but they exist as inert display replicas (like .50 BMG), specialized novelty items, or experimental projectiles in shotgun shells (using sabot/wad systems) for specific uses like clay shooting, offering high strength but challenges for rifled barrels. While titanium is strong and light, it’s difficult to machine into precise bullets, tends to scratch barrels without a sabot, and lacks the mass of lead for effective impact, making it poor for standard ammunition but great for unique, displayable bullion. Titanium-core bullets:

- Are nearly half the weight of steel

- Maintain high structural strength

- Deliver high velocity and penetration

- Lose energy rapidly after impact — reducing collateral risk

3. Depleted-Uranium (DU) Rounds

Depleted uranium is a nuclear-fuel by-product used in armor-piercing ammunition. DU cores self-sharpen on impact, significantly improving penetration. They are used primarily in crew-served and anti-armor systems. Depleted uranium (DU) rounds use a dense, leftover metal from nuclear fuel processing, prized for their ability to pierce tank armor, ignite on impact, and self-sharpen for maximum penetration, posing health/environmental concerns due to toxicity and radioactivity when dispersed as dust. Used by militaries in conflicts like the Gulf Wars, Kosovo, and Iraq, these rounds contain less radioactive but still potent uranium isotopes, making them effective but controversial.

4. Lead-Free / Frangible Ammunition

Lead-free frangible ammo are specialized bullets made from compressed powdered metals (like copper, tin, tungsten) mixed with binders, designed to disintegrate into dust upon hitting hard surfaces (steel targets, concrete) instead of ricocheting or creating dangerous shrapnel, making them ideal for indoor ranges, close-quarters training, and reducing environmental lead, often including non-toxic primers for a fully lead-free experience. Advantages include:

- No ricochet

- Rapid fragmentation

- Reduced collateral hazard

Ideal for CQB and training environments.

5. Flechette Ammunition

Flechettes are fin-stabilized steel darts, sometimes packed in groups (e.g. 20 per cartridge). Flechette ammunition remains relevant with modern improvements for tighter patterns (like M1A8) and specialized military use (like Navy helicopter darts) for anti-personnel/light armor, offering kinetic energy impact without explosives. They offer:

- High penetration

- Flat trajectory

- Effectiveness through vegetation

These rounds are well-suited for anti-sniper and jungle operations.

6. Development of .300 Blackout (BLK)

The .300 AAC Blackout also known as 7.62×35mm is a carbine cartridge developed in the United States by Advanced Armament Corporation (AAC) for use in the M4 carbine. Its purpose is to achieve ballistics similar to the 7.62×39mm Soviet cartridge in an AR-15 while using standard AR-15 magazines at their normal capacities.

.300 BLK (7.62×35 mm) has become increasingly popular for special operations, offering:

- Superior stopping power compared to 5.56 mm

- Excellent subsonic performance with suppressors

- Enhanced lethality in CQB

It bridges the capability gap between 5.56 mm and 7.62×39 mm.

Summed Up

The evolution of small arms has transitioned from the Mechanical (solving ignition) to the Ballistic (solving range and accuracy) and finally to the Integrated (solving the human error through digital fire control). While the core concept of a chemically propelled projectile remains, the leap from the 10th-century fire lance to the 21st-century XM7 represents an increase in lethality that has redefined the infantry’s role in global conflict.

References:

- Small arm | Types, Descriptions, History, & Facts | Britannica

- History of the firearm – Wikipedia

- Small but Deadly: The Minié Ball – Gettysburg College

- The Emergence of Smokeless Powder – Kirammo

- .277 Fury Ballistics – SIG Sauer/Wikipedia

- Military Tactics and Doctrine Lags Behind Technology – MSG John W. Keene