By the summer of 1944, the Second World War had entered a paradoxical phase. The Allies were winning, Normandy had been breached, Paris was within reach, and German defeat was no longer a question of if, but when. Yet some of Nazi Germany’s most dangerous military assets remained stubbornly intact. Reinforced U-boat pens along the French coast, buried V-weapon launch facilities, and concrete bunkers engineered to withstand the heaviest bombs defied repeated air attacks. Conventional bombing, even at enormous human cost, was proving insufficient.

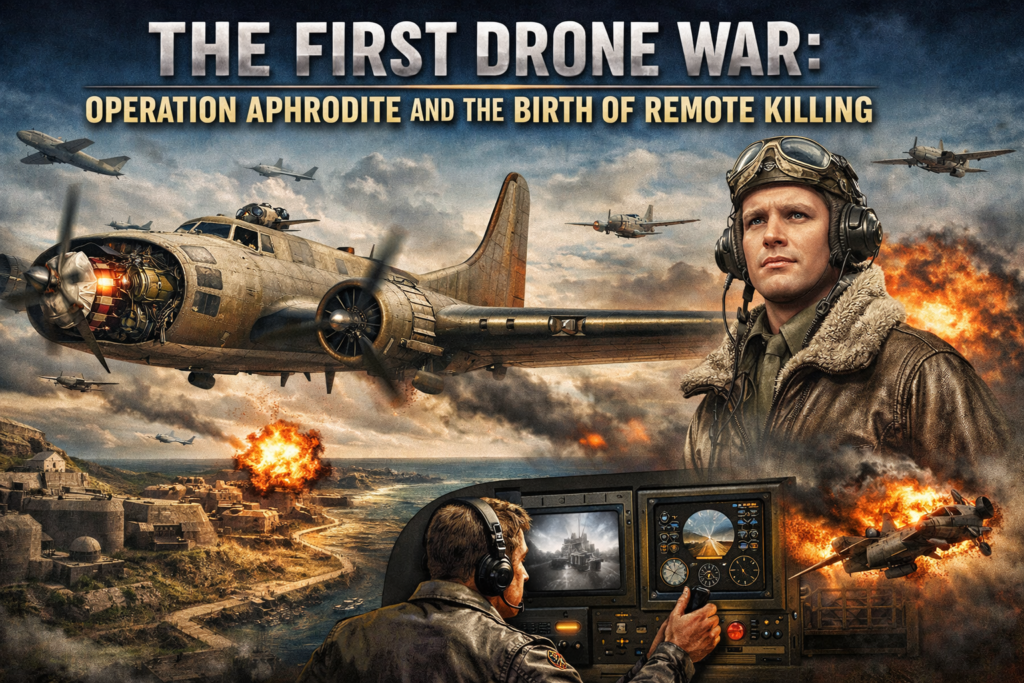

Inside Allied command rooms, frustration turned into innovation. If pilots could not survive flying close enough to destroy these targets, perhaps aircraft could be sacrificed instead. From this strategic desperation emerged an idea so radical that it sounded almost like science fiction: turn entire bombers into remotely controlled flying bombs. Thus began Operation Aphrodite, history’s first true attempt at drone warfare; decades before the word “drone” would enter common military vocabulary.

Old Bombers, New Purpose

Operation Aphrodite was a bold and unprecedented World War II initiative launched by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) in 1944, aimed at overcoming the limitations of conventional bombing against Germany’s most heavily fortified targets. The program sought to repurpose worn-out Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers into remotely controlled aerial weapons, effectively early “kamikaze drones” capable of delivering massive explosive payloads against hardened V-weapon installations, including V-1 and V-2 launch and storage sites that had proven resistant to repeated high-altitude bombing attacks. Formally authorized on 23 June 1944 by the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe (USSTAF), the project involved converting these aircraft into the BQ-7 configuration and loading them with up to 21,000 pounds of Torpex, a high-yield explosive significantly more powerful than TNT.

Because fully autonomous flight was beyond the technological capabilities of the era, each BQ-7 was initially flown by a volunteer pilot and flight engineer who took off from airfields in England, climbed to a pre-designated altitude, armed the explosive charge, and then bailed out over the sea. Control of the aircraft was subsequently transferred to remote operators flying in escort aircraft often de Havilland Mosquitos who guided the drone toward its target using radio-control systems and live television camera feeds installed in the bomber’s nose and cockpit. This combination of remote visual guidance and radio command marked one of the earliest attempts at human-in-the-loop aerial strike warfare.

The origins of Operation Aphrodite lay in the urgent Allied requirement to neutralize Nazi Germany’s V-weapon program, which posed a growing threat to cities, ports, and advancing Allied forces. Conventional bombing methods, even when conducted in mass formations, consistently failed to achieve decisive results against deeply buried bunkers and reinforced concrete structures. Operating under the oversight of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, Aphrodite built upon earlier experimental work in radio-guided munitions and ran parallel to the U.S. Navy’s closely related Operation Anvil, which employed similarly modified PB4Y-1 Liberator aircraft.

The first operational missions were flown on 4 August 1944, when four BQ-7 drones were dispatched against V-1 launch sites in northern France under heavy fighter escort. These initial attempts, however, exposed the fragility of the system. Faulty radio beacons, unreliable autopilot components, and intermittent television signals frequently caused drones to veer off course or crash before reaching their targets, while in some cases explosives detonated prematurely or failed altogether.

The program’s most tragic episode occurred on 12 August 1944 during an Operation Anvil mission against the German V-3 supergun complex at Mimoyecques, France. Lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., the eldest brother of future U.S. President John F. Kennedy, was piloting the lead BQ-8 when the aircraft suffered a catastrophic mid-air explosion shortly after takeoff, likely triggered by an electrical malfunction that ignited the Torpex payload. Kennedy and his co-pilot were killed instantly, casting a long shadow over both Aphrodite and Anvil and underscoring the extreme dangers inherent in early remote-control warfare.

Subsequent missions, including attacks on U-boat pens at Heligoland and other heavily fortified coastal targets in September 1944, produced similarly disappointing results. Poor weather, limited guidance accuracy, and persistent technical failures meant that most drones missed their intended objectives or were lost before impact. By early 1945, after approximately 14 missions with negligible tactical success, Operation Aphrodite was formally terminated in April 1945. Advancing Allied ground forces had already captured many of the targeted sites, and more reliable bombing techniques had rendered the experimental program strategically redundant. Although costly and largely ineffective in immediate military terms, Aphrodite exposed the foundational challenges of drone warfare and left a lasting imprint on postwar research into guided munitions and remotely piloted aircraft.The aircraft chosen for Aphrodite were not cutting-edge machines. They were tired veterans of the air war; B-17 Flying Fortresses and PB4Y-1 Liberators that had survived flak-filled skies over Germany but were nearing the end of their operational lives. Instead of scrapping them, engineers proposed something unprecedented: strip them of guns, armor, and unnecessary equipment, and replace their bomb loads with up to 20,000–21,000 pounds of Torpex, an explosive significantly more powerful than TNT.

Once modified, these aircraft were redesignated BQ-7 (B-17s) and BQ-8 (PB4Ys). They were no longer bombers. They were weapons, giant, pilot-guided missiles before missiles truly existed. But one problem remained unsolved: machines in 1944 could not take off by themselves.

The Most Dangerous Takeoff in Aviation History

Operation Aphrodite carried a cruel irony. Although designed to reduce aircrew casualties, its most lethal phase required human pilots. Each drone aircraft carried a two-man volunteer crew; a pilot and flight engineer, whose task was to take off, climb to altitude, stabilize the aircraft, arm the explosives, and then bail out over friendly territory.

Only after the crew parachuted clear would the aircraft become truly unmanned. The concept demanded extraordinary courage. Flying an aircraft packed with over ten tons of volatile explosives, knowing a single malfunction could mean instant annihilation, required more than duty; it required belief in the future of warfare.

Once airborne, control would shift to a “mother ship”, typically a modified B-17 or B-24 flying nearby. From this aircraft, a remote operator would guide the drone toward its target using radio signals and astonishingly live television images.

One of Aphrodite’s most remarkable innovations was its use of onboard television cameras, a technology barely out of its experimental phase. Each drone carried two black and white cameras: one pointed forward to show the approaching landscape, and another focused on cockpit instruments so the remote operator could monitor altitude and heading.

The grainy images were transmitted via radio link to a screen inside the mother ship. For the first time in history, a human being attempted to guide a lethal weapon using a remote visual feed; the conceptual ancestor of today’s drone cockpit screens in Nevada or Creech Air Force Base.

Yet the technology was fragile. The resolution was poor, the frame rate slow, and radio interference common. Clouds, smoke, or even sunlight glare could blind the operator. Precision, by modern standards, was almost impossible. Still, the idea was revolutionary: separate the warrior from the battlefield, but keep the decision to kill in human hands.

The Death That Defined the Program

The most tragic moment in the history of Operation Aphrodite occurred on 12 August 1944, and it would forever define the program in public memory. Lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., eldest son of Joseph Kennedy and older brother to future U.S. President John F. Kennedy, had already completed a full combat tour. Yet he volunteered for Operation Anvil; the Navy’s parallel program to Aphrodite—believing the mission could shorten the war and save lives.

Kennedy’s aircraft, a PB4Y-1 Liberator converted into a BQ-8, lifted off from England loaded with over 21,000 pounds of Torpex. Somewhere over Suffolk, before Kennedy and his co-pilot could bail out, the aircraft exploded without warning. The blast was so immense that wreckage scattered across the countryside. There were no survivors.

The shock reverberated through the U.S. military. A program intended to protect aircrews had killed one of America’s most prominent young officers in its most dangerous phase; the moment before the aircraft even became unmanned. It was the darkest irony of early drone warfare.

Despite the death of such a high-profile pilot, many more missions were flown before Operations Aphrodite and Anvil were shut down. On January 27, 1945, Gen. Carl Spaatz sent a dispatch to Doolittle, saying, “Aphrodite babies must not be launched against the enemy until further orders.”

The End of Aphrodite—and the Survival of an Idea

Following Kennedy’s death and continued mission failures, confidence in Aphrodite collapsed. By late 1944, Allied ground forces were overrunning many intended targets anyway. The program was quietly terminated.

By every immediate military metric, Operation Aphrodite was a failure:

- No hardened target destroyed as intended

- Multiple aircraft lost

- Highly trained volunteers killed

- No tactical advantage gained

And yet, something profound had occurred. For the first time, war planners had demonstrated that aircraft could be controlled remotely, that visual data could guide weapons from afar, and that humans could project lethal force without being physically present at the point of impact. The seed had been planted.

From Flying Bombs to Silent Hunters

Decades later, when the MQ-1 Predator appeared over the Balkans and later Afghanistan, it did not represent a radical break from history—but the fulfillment of an unfinished idea. Where Aphrodite relied on analog radio and crude television, Predator used satellite links, GPS, and stabilized electro-optical sensors. Where Aphrodite was expendable, Predator was persistent.

The MQ-9 Reaper completed the transformation. No longer experimental or improvised, unmanned strike aircraft became central to U.S. doctrine; capable of surveillance, target identification, and precision killing, all controlled by operators thousands of miles away. The philosophical thread remained unchanged since 1944: remove the pilot from danger, but not from responsibility.

A Legacy Beyond Technology

Operation Aphrodite also foreshadowed the ethical dilemmas that define modern drone warfare. Questions first encountered in grainy television screens over Europe now dominate strategic debate:

- Does distance make killing easier?

- Who bears responsibility for remote strikes?

- How much autonomy is too much?

These debates did not begin in the 21st century. They began when a remote operator, staring at a flickering black-and-white screen, tried to guide an explosive-laden bomber toward a German bunker in 1944.

Conclusion: The War Before the Drone Age

Operation Aphrodite was not a success, but it was a threshold. It marked the moment when warfare crossed from manned courage into technological abstraction. The men who flew those explosive aircraft were not casualties of failure; they were pioneers operating decades ahead of their time.

Every modern drone strike, every remote ISR mission, every debate about autonomous warfare carries the faint echo of those B-17s and PB4Ys; engines humming, explosives armed, control handed off to a flickering screen. The first drone war was fought not with silicon and satellites, but with courage, wires, radio waves, and the dangerous belief that the future of war had already arrived.